What Is The Mind Body Connection?Since the intention of this blog is to explore the many facets, practices and benefits of natural health and healing, it seems apt to begin our journey with a discussion of a central pillar of natural healing: the mind body connection...

The Mind Body Connection: Finding Health In An Age Of Stress

What Is The Mind Body Connection?

Since the intention of this blog is to explore the many facets, practices and benefits of natural health and healing, it seems apt to begin our journey with a discussion of a central pillar of natural healing: the mind body connection

In this article we’ll look at some of the major ways the mind and body are connected, reviewing the scientific evidence supporting this vital link. We’ll explore the mind body connection from a bio-psycho-social viewpoint, appreciating how your physical and social environment, psychological state and body physiology interact to support or disturb health

We’ll learn how the body reacts to stress, the influence of coping and positive emotions on health, and discuss the contribution of mind-body and other holistic approaches from yoga, mindfulness and creative visualization to acupuncture and cognitive behavioural therapy, to maintaining optimum health through the mind body link

From fighting infection to cardiovascular health and the quality of your digestion, understanding the mind body connection is a vital first step to help you take control of your wellbeing for a happier and healthier life

How The Mind And Body Are Connected

While it’s not difficult to appreciate how physical illness and pain can impact you emotionally, understanding how a mental state can aggravate your gut or increase your blood pressure needs rather more clarification

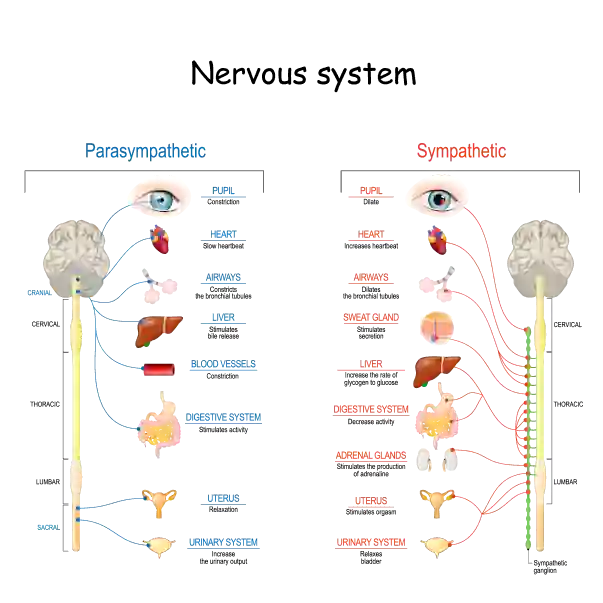

The key to understanding how the mind and body are linked lies in the body’s three great regulating systems:

- 1 – The Nervous System

- processes data and regulates all bodily functions on a moment to moment basis through electrical impulses travelling along nerves

- 2 – The Endocrine System

- regulates physiology over days, weeks or months by means of circulating messengers known as hormones. Finally

- 3 – The immune system

- distinguishes between self and other to keep us safe from external and internal invaders, including bacteria, viruses and malignant cells

Though the functions of nervous and endocrine systems have long been considered to be integrated, the immune system was thought to work autonomously until, the 1970’s, psychologist Robert Ader and Nicholas Cohen, currently professor Emeritus of microbiology and immunology and of psychiatry at Rochester University (USA), demonstrated that immune responses can be conditioned and are thus under the influence of the brain. Thus, Ader and Cohen established the modern discipline of psycho-neuro-immunology, finally integrating all three systems into a single supersystem orchestrating the body’s need to maintain stability and health in an ever changing environment

Another factor of importance for regulating whole-body physiology is the microbiome, the colonies of micro-organisms living in on and in our bodies. The gut microbiome in particular has been shown to play a central role not only in digestive health but also in psychological wellbeing

A great starting point for understanding how mental states affect physical health is by studying how the body responds to stress

Stress And Health

The General Adaptation Syndrome

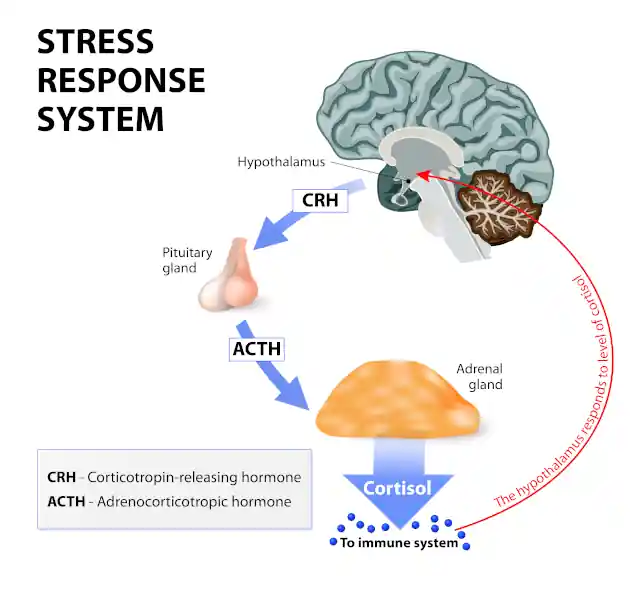

First described by the endocrinologist Hans Selye in 1936, the body responds to stress with a series of hormonal and neural signals he called the General Adaptation Syndrome, or GAS

Dr Selye noted that when we appraise any situation as challenging, the body mounts a stereotypical response by way of a cascade of hormones originating in a brain region known as the hypothalamus, and culminating in the release of the steroid hormone cortisol from the adrenal glands

In its acute (short term) phase this adaptation to stress is essential for survival. Cortisol raises blood sugar and provides the body with the resources it needs to respond effectively to a stressor. In the long term, however, persistently elevated cortisol levels are associated with a broad range of health issues, including cardiovascular disease and stroke, peptic ulcers, inflammatory bowel disease and more

Stress And The Nervous System

At the same time as releasing cortisol, stress also triggers a fight-flight-freeze response through the sympathetic nervous system via chemical mediators which include the hormone adrenaline and neurotransmitter noradrenaline

Like the Cortisol response, sympathetic activity mobilizes the body into action to deal with stressors, raising blood pressure, quickening the heart and stimulating breathing in readiness for action. Also like Cortisol, fight-and-flight activity is pro inflammatory

Unlike the cortisol effect, however, the adrenaline-noradrelaine effect is short term, more strongly associated with positive stress-avoiding action, and has fewer long-term consequences on health

Stress And Inflammation

A significant consequence of stress on health is inflammation. Inflammation is one of the most basic responses of innate immunity for protecting us against injury and disease. During inflammation the immune system releases chemical mediators which attract immune cells to deal with invaders, damaged tissues or rogue cells. While protective in the short term, inflammation can, when excessive, prolonged (chronic) or inappropriate (eg. auto-immunity) damage the body’s own tissues, leading to problems ranging from intestinal and joint inflammation to blood-vessel damage and depression

While in the short-term stress tends to dampen inflammation and boost immunity (cortisol analogues are used clinically for their anti-inflammatory effects), persistently raised cortisol levels suppresses immune activity while raising inflammation. Chronic inflammation has been linked to a wide range of issues, including

- Bronchospasm in asthma

- Intestinal inflammation (Chrohn’s, Ulcerative Colitis, Coeliac’s) with pain, diarrhoea and impaired absorption

- Arthritis with joint swelling with pain

- Blood vessel damage with deposition of fibro-fatty plaques (atheroma) predisposing to heart disease and stroke

- a range of mental health issues, including depression

Neuroinflammation is an inflammatory response mediated specifically by cells within the brain and spinal cord. By triggering neuroinflammation stress has been shown to be a factor in a number of mental health issues, including depression and schizophrenia. Studies show that stressful life experiences are associated with raised pro-inflammatory chemical mediators (cytokines) in childhood, as well as a higher risk of mental illness in adulthood (Calcia 2016)

A literature review by Viktoriya Maydych (2019) finds that current research supports a direct link between stress, inflammation and reduced emotional attention, the triad itself being a predictor for depression

Coping With Stress

Not all of Hans Selye’s findings have been borne out by research. Later research has found that, depending on the individual’s appraisal of a stressor, the stress response may be short term, triggering sympathetic nervous system responses, longer term, triggering cortisol release, or both

Crucial to stress coping is the extent to which you feel you have the resources to deal with the stressor, and the kind of outcome you expect. Thus, feeling you can deal with a stressful situation and expecting a positive outcome is linked to short-term arousal, while feeling hopeless, helpless and generally having little control, along with expectation of a negative outcome is linked to longer-term cortisol mediated arousal

Inevitably, individual personality traits and past experiences of stress, especially during childhood, all play a significant role in stress coping

Not surprisingly, the body has an inbuilt natural relaxation response mediated by the parasympathetic nervous system, the complement of the sympathetic system, having largely opposite effects, though it would be more accurate to consider the two systems as complementary

The parasympathetic system works to repair tissue damage and replenish the body’s resources depleted by stress, calming the heart and breath, lowering blood pressure and stimulating digestion, assimilation and excretion of wastes. Parasympathetic activity is also actively anti-inflammatory

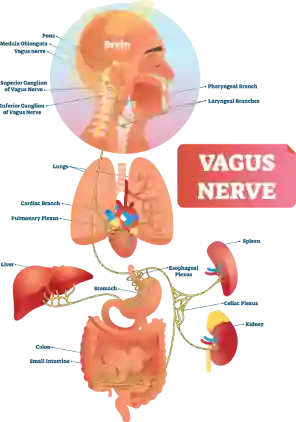

Rest-and-digest responses are mediated primarily via the Vagus nerve, so called because of its long, wandering course from the brain stem to virtually every organ in the body

Parasympathetic Vagal activity is triggered by an appraisal of a situation as inherently safe. Stimulation of the Vagus has lately been hailed as the holy grail of instant rest-and-digest. External electrical stimulation of the Vagus in the neck, while effective, is a specialist surgical procedure reserved for the management of treatment resistant epilepsy and clinical depression. While reflex and mechanical stimulation of the vagus using stimuli including pressure and cold applications are advocated by some, their usefulness remains spurious

The connection of parasympathetic activity to safety, on the other hand, opens the door to a plethora of possible interventions, including yoga, mindfulness, creative visualization and psychological methods such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), all of which attempt to enhance stress coping, foment positive mental states and generally stimulate the rest-and-digest system using the mind body connection to exert their positive effects

Scientific Evidence

For Mind-Body Therapies

Modern health research increasingly takes a bio-psycho-social stance on health and disease. The model replaces the old biomedical approach which sought to understand disease solely by looking at biological factors, with a broader understanding where personal history, lifestyle choices and the social and physical environment interact with biological processes to support or perturb health

This more holistic perspective is strongly supported by research. Where studies show that chronic stress is linked to many common health issues of our day, including cardiovascular disease, obesity, and autoimmunity, they also strongly support the effectiveness of interventions which promote relaxation and positive mental states to enhance immune activity, reduce inflammation and provide a whole range of positive physical and mental health outcomes

Having already looked at the effects of stress and coping with stress on health, we can now consider the evidence for positive emotions on wellbeing

Positive Emotion, Coping And Health

More recently, research has focused on the mind body link in the context of positive emotions. Studies supports the theory (Fredrickson, 1998) that emotions like optimism, curiosity, joy and love help to broaden an individual’s thought–action repertoire, prompting them to let go of automatic behaviours in favour of novel, creative thoughts and actions. This leads to a building of personal resources for dealing with current and future stressful events, as well as helping to undo some of the harmful effects of negative emotions

A number of subsequent studies have supported the role of positive emotions (Fredrickson, Cohen et al, 2000-2008) in coping. People who score highly for resilience – the ability to bounce back from and adapt to the demands of distressing events – experience more positive emotions, deriving positive meaning from day to day stressors. At the physical level they also also demonstrate faster rates of cardiovascular recovery (slowing of the heart, lowering of blood pressure) following laboratory induced stressful events (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004).

Nor are positive emotions linked solely to the expectation of a positive outcome. Folkman (1997) found that positive emotions can also arise from events with unfavourable outcomes, provided the individual can find meaning or benefit arising from their experiences

The ability to find benefits from difficult experiences has been linked to reduced distress following bereavement, heart attack and exposure to disasters, including damage to property and loss of life (Tennen & Affleck, 1999).

Benefit-finding has been linked to better physical health outcomes, ranging from a lower propensity to re-infarction following a first heart attack, to reduced pain and improved mobility in inflammatory arthritis

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

CBT works on the reciprocal relationship between cognition (thinking) and behaviour, helping individuals identify and change habitual thought patterns using a range of activities, such as being in the present moment (mindfulness), relaxation and reframing of negative thought patterns

CBT works on positive emotions by helping individuals to identify the negative assumptions underlying their thinking, consciously nurturing positive thoughts and behaviors until these become the new norm

By improving self awareness, reducing negative thoughts and developing better coping skills CBT helps to reduce anxiety and improve emotional resilience. Studies show that CBT can help with anxiety, depression, panic attacks, phobias and post-traumatic stress. CBT has also been used successfully in obsessive compulsive disorders and a range of eating disorders. Physical health benefits include relief from chronic pain, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue, as well as a range of physical disorders with a strong psychological component, such as irritable bowel

Yoga And Mindfulness Based Approaches

For Health And Happiness

Yoga And Meditation

Yoga and meditation are mindfulness-based practices promoting self-awareness, relaxation, and resilience, and have been shown to enhance the whole spectrum of bodily and emotional health

Research consistently shows that people who practice yoga report lower levels of anxiety, depression, and stress, and experience significant improvements in physical fitness parameters such as flexibility, strength, and cardiovascular endurance

Yoga has been shown to improve all the major risk factors for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular (stroke) disease, reducing blood pressure, and improving blood cholesterol profile. Improvements have been found in respiratory function, chronic pain management and stress coping, leading to a reduction in circulating stress hormones while stimulating rest-and-digest

Want to see for yourself how yoga works? Join one of our weekly yoga classes to help you maintain a healthy spine and allow your mind and body to rest and digest

Breath Work

Breath work is an integral part of yoga practice. Life force, or vital energy (prana) manifests in the body as breath, and in the mind as thinking and feeling. Breathwork in yoga is known as pranayama: control of the vital force. Thus, when the mind is excited (through joy or distress) the breath is quick, sometimes erratic. When the breath is quiet the emotions are calm and the mind is clear and relaxed

Quiet breathing (Zaccaro, 2018) has been linked to objective measures of parasympathetic activity, such as increased heart-rate-variability (HRV is the difference in heart rate during inhalation and exhalation and is a measure of Vagal tone), as well as the subjective experience of relaxed wellbeing. Though the precise mechanisms remain under review, breath affects mental wellbeing by at least two pathways: an interoceptive (ability to perceive the state of the inner body) mechanism related to sensors in the breathing apparatus, likely mediated by the Vagus nerve, and receptors within the nose signalling directly to emotional centres in the brain

Creative Visualization And Guided Imagery

An intrinsic practice in yoga and other mindfulness approaches, visualization has been shown to provide tangible health benefits associated with the systemic relaxation response mediated by the parasympathetic system and Vagus

Brain imaging techniques show that visualization stimulates the brain areas involved with inner perceptions as if they were actually happening. In the same way that the stress response can be triggered by the mere anticipation or memory of a stressor, the relaxation response can be elicited through techniques such as yoga nidra, a guided practice using body and breath mindfulness, and progressing through various stages of creative visualization to reach the deepest possible level of relaxation while remaining awake

Mindfulness

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) are modern takes on traditional Buddhist meditation with a very strong evidence base. Initially developed to manage stress and depression respectively, mindfulness helps develop positive emotions, resilience and cognitive function, while also exerting positive effects on physical health through the mind body connection, including a reduction in blood pressure and circulating stress hormones

The Gut Brain Axis:

Health, Nutrition And The Microbiome

The role of nutrition in health, though crucial, is beyond the scope of this article. One aspect of nutrition, however, is so pertinent to our discussion of the mind-body link that I would be negligent to ignore it. It concerns the microbiome, those trillions of bacteria and other micro-organisms living on every square inch of the surface of your body, from the lining of your gut and lungs to your skin, nails and even eyelashes, and one of the hottest topics in current health science

In an age of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance, where anti-microbial products find their way into everything from cleaning materials to items of clothing such as socks (it’s supposed to stop them from smelling), the role of “good” bacteria in health has become an imperative

As mentioned, the gut houses colonies of micro-organisms essential for health. Though the subject is too large to cover in a couple of paragraphs, there are some major topics worth discussing in relation to the mind body connection

The first is the gut-brain axis, a two way connection between gut and brain. We’ve described the vagus nerve as the main carrier of rest-and-digest activity from the brain to the organs. Yet 80% of Vagal nerve fibres are sensory, carrying information from the organs to the brain. And since, in terms of surface area, the gut is the largest organ in the body, a good part of the vagus is dedicated to listening to the gut

Gut bacteria produce more than 90% of the body’s serotonin, a chemical transmitter involved in mood and wellbeing (low serotonin levels have been linked to clinical depression), as well as digestive function, and previously thought to be largely confined to the brain.

In addition to serotonin bacteria manufacture health-promoting substances such as butyrate and propionate, short chain fatty acids with an important role in supporting immunity and down-regulating inflammation

Though the health of the gut microbiome is influenced by numerous factors, the effects of diet are unquestionable. A picture is emerging of optimal gut health depending not just on a large number of organisms, but also a wide variety of different species

Pro-biotic foods containing live or dormant bacteria can help replace beneficial bacterial colonies. Probiotics include fermented products including yoghurt, kefir and kombucha as well as bean and vegetable ferments such as miso, sauerkrout and kimchi

While directly supplying beneficial bacteria, studies show that commercial pro-biotics deliver a rather narrow range of species with limited benefits. Pre-biotics, on the other hand, provide the nutrition necessary for good bacteria to thrive, and have been shown to support a microbiome with much greater diversity. And the most abundant and effective pre-biotic? Fibre

The bulk of the fibre we ingest is cellulose, an insoluble carbohydrate which our digestive system is unable to break down. Fibre is, however, food for microbiotic organisms. In a beautiful display of symbiosis (a relationship of mutual benefit) our friendly microbes break down and feed on fibre while releasing by-products essential for our physical and mental wellbeing

Thus, a high fibre diet, one rich in whole grains, pulses and vegetables is one of the very best ways to support your friendly gut bugs, allowing them to thrive and provide in return a bounty of health and happiness

Holistic Body Therapies

For A Healthy Mind And Body

The contribution of body-work to your psycho-somatic wellbeing is well documented. Holistic body therapies, including holistic massage, Rolfing, shiatsu, tuina, chiropractic and osteopathy, all embrace the philosophy of body-mind unity

As an osteopath, I’d like to round off this article with a mention of the place of osteopathy within mind-body medicine. There is a general idea in the popular mind that osteopathy is a form of manual therapy primarily aimed at relieving back and sundry other aches and pains. While we hopefully do a decent job of helping your body to heal, osteopathy is a holistic system of healthcare which works with your structure for the sake of total physical and mental wellbeing. Osteopaths aim to create an optimal physical environment for all your vital functions to thrive

Osteopaths work with the functional and structural relationships between the musculo-skeletal system (soma), internal organs (viscera), and psyche (mind), with the spine as principle mediator between the brain and body

It’s no coincidence that of the list of conditions the profession can help with, according to available evidence, share the same characteristics as other therapies working within the mind-body spectrum

You can read more about osteopathy and some of the conditions osteopathy can help you with by clicking the link

Where historically acute, especially infectious, diseases have been the dominant cause of ill health and death, the modern age has seen a shift towards chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity and cancer

Modern scientific medicine has indeed produced virtual miracles in curing and eradicating infectious disease and increasing human life-spans beyond anything we ever dreamed possible. Yet an exclusively bio-medical approach has fallen short of addressing the epidemic of chronic physical and mental health issues resulting from factors such as social isolation and stress

As the limitations of an exclusively bio-medical view of health and disease become increasingly apparent, the need to bring the psyche into the picture is ever more pressing. Neither do the mind and body operate in a vacuum, but rather within a complex set of interacting factors which includes personal history, job satisfaction, family and social relationships, coping strategies, diet and access to clean air and water, to name just a few

More than ever, there is a pressing need to address the health challenges of our day from a more holistic, ecological perspective, with the body, mind and environment as essential components and the individual at the centre of her wellbeing

References

- Yun-Zi Liu et al, (2019). Inflammation: The Common Pathway of Stress-Related Diseases.

- M A Calcia et al, (2016). Stress and neuroinflammation: a systematic review of the effects of stress on microglia and the implications for mental illness

- Fredrickson, B.L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300–319.

- Cohen, M.A., & Fredrickson, B.L. (2006). Beyond the moment, beyond the self: shared ground between selective investment theory and the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Psychological Inquiry, 17, 39–44

- Fredrickson, B.L.et al, (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving kindness meditation build consequential personal resources

- Fredrickson, B.L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13, 172–175.

- Fredrickson, B.L., & Levenson, R.W. (1998). Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 12, 191–220.

- Fredrickson, B.L., Mancuso, R.A., Branigan, C., & Tugade, M.M. (2000). The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 24, 237–258.

- Fredrickson, B.L., Tugade, M.M., Waugh, C.E., & Larkin, G.R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 365–376.

- Michele M Tugade, B L Fredrickson (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J Pers Soc Psychol 86(2):320-33

- A Zaccaro et al (2018) How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing

The Mind Body Connection: Finding Health In An Age Of Stress

Yoga And Mindfulness For Dysfunctional Breathing: 5 Exercises For Better Health

Did you know breathing too much carries a health warning? Beyond gas exchange, how you breathe affects all your systems, from digestive and cardiovascular function to emotional health

Science Of Healthy Breathing: How To Recognize And Manage Breathing Pattern Disorder

How you breathe not only serves not just to drive energy production, but also impacts your whole emotional as well as physical well-being